This is an African Robots vs SPACECRAFT project by Ralph Borland, working with Jason Stapleton of Ambient3D for 3D and VR, Sean Devonport for sound, and wire artists Lewis Kaluzi, Farai Kanyemba and Franco Shidume. Rick Treweek of Eden Labs is providing additional VRChat consultation. More about us below.

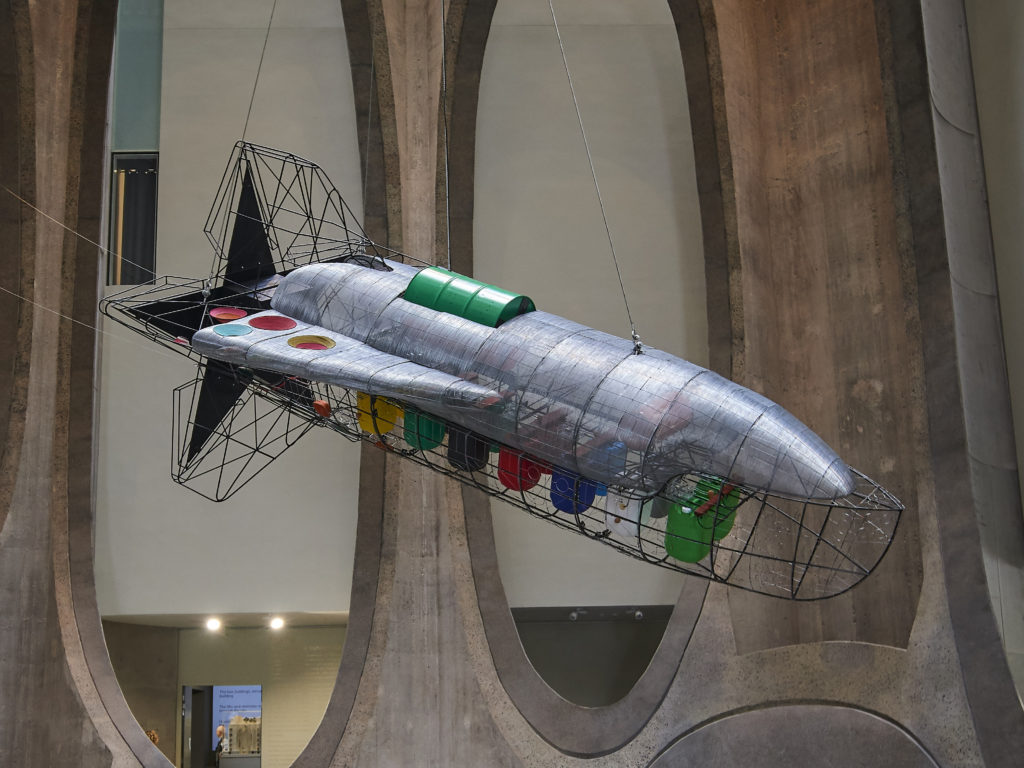

Digi-Dub Club extends the artwork Dubship I – Black Starliner (2019 – ongoing) a monumental music-making wire art spaceship sculpture launched at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art in Cape Town in 2019, into shared Virtual Reality social space on the platform VRChat. Dubship I – Black Starliner refers to the history of the Black Star Line shipping company, founded by the Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey in 1919 as part of his project for advancing black political and economic power and the succour of the African diaspora; his work’s memorialisation through dub music; and space travel as a metaphor for political and spiritual liberation, as seen in funk, hiphop, dub and science fiction.

VRChat is a platform for social interaction in Virtual Reality ‘worlds’ (25,000 and counting). It transforms VR from a solitary experience to a shared experience, in which participants can explore thousands of VR spaces while interacting with other participants via voice and gesture. To participate, a personal computer and internet connection is the minimum requirement, though a VR headset allows the full immersive experience. 2020 has brought increased attention to VRC, with events such as the Venice International Film Festival hosting a VRC section, along with festivals such as Raindance, and the HBO TV show Lovecraft Country. Read an interesting article by the developers of Venice VR Expanded here.

This new VRChat world Digi-Dub Club centres on an animated 3D scan of the sculpture at the heart of the work to create a sonified, interactive social space – a compelling environment in which people can socialise and interact with the work and the issues it engages with. Designing the space is like designing for a social club, activist space, and a party – it takes place in an otherworldly environment, a night-time desert environment under a canopy of stars, with a fire to gather around, and a modified shipping container club, the Black Star Bar, that will serve variously as library, exhibition space, DJ booth, and bar.

Phase I of the project is supported by the African Culture Fund’s Solidarity Fund for Artists and Cultural Organizations in Africa. It launches on Friday 6 November with Kalashnikovv Gallery at Art Joburg – you can visit the VRChat world at the link below, and we have shot a rough video walkthrough and posted it below too.

Digi-Dub Club in VRC

For our future plans for the work, read under Phase II below (and see an illustrated concept note for an easy overview)

Read further down the page for more about what makes our take on Virtual Reality special, what the term ‘digi-dub’ describes, the original (and evolving) sculpture Dubship I, and more besides!

Phase II

We are seeking support to extend our work with Digi-Dub Club as a VR work back into physical space, to create a blended-reality work centred on a real-life modified shipping container housing twin VR access points. This real-life shipping container is mapped to the VR shipping container in Digi-Dub Club, the Black Star Bar.

The VR stations can also be used as production tools, and the physical sculpture Dubship I dismantles to fit inside it. The container equips the project to travel across geographical borders, where it accompanies the sculpture as an exhibition and social space, and it provides access to the shared VR social space for remote interaction. Phase II enables the mobility of the artwork in both physical and virtual space.

Here is an illustrated concept note for the extended proposal.

More about Phase II

This is a proposal for a virtual reality artwork and social space in the virtual reality social world VRChat, accessed through a repurposed shipping container housing twin VR stations. Putting on one of the headsets transports you into a virtual version of the same space, in a VR landscape, in which you can interact with other people from anywhere in the world – as well as the person in the other VR station alongside you (as avatars in the VRChat world).

As well as offering a VR portal, the shipping container can transport over borders the large-scale, interactive sound-system sculpture at the heart of this work, Dubship I – Black Starliner (2019). Where this is exhibited, the container functions as an accompanying VR space, and can take other functions as needed: library, exhibition space, meeting place, DJ booth, secure lockup etc.

Two people can enter the same VRChat world we will design as the Digi-Dub Club, accompanying each other into a space where they can meet new people from other places. The Digi-Dub Club contains a virtual container bar, like the physical installation, blending the physical and virtual experiences. The container functions as a portal into the VR club.

With the headset on, putting out your hand to touch the wall of the virtual container, you will encounter the wall of the physical container. ‘Walking’ out the container (with your hand controllers) you will be in a virtual world in which you’ll find the Dubship sculpture, remodelled in 3D. We will be designing the landscape and interactive features, and placing VR sculptures produced by wire artists using the VR stations as production tools.

This project will be doing a few unusual things, performing some pleasing inversions of normal functionality for VR and for shipping containers. Inversions are related to détournements, the interventionist art mode for changing the meaning of existing forms to communicate new perspectives. The Black Star Line inverted the meaning of the trans-continental ship, from tool for colonial extraction, to means of empowerment and return.

A shipping container in normal use itself travels across geographical space, transporting its contents to other physical spaces. In our setup as VR station, people enter a stationary shipping container, and are transported to a virtual space, where they can meet and interact with people from other geographical spaces. The shipping container transports, in a different way to normal.

In VRChat, users can assume the form of many avatars at will. Some users will have their own custom avatars they habitually use, but any user can in seconds select from a wide range of avatars that are freely available, and shift the way they appear to other users. In our setup, users will enter and inhabit one of a pair of custom avatars designed for our world. These are the hosts of Digi-Dub Club – avatars that will host many users in sequence as they enter and explore the world. This is an unusual situation in VRChat in which one avatar represents many users, and will present interesting opportunities and challenges in communicating this to others.

The VR gear we acquire for the project can also be used for production of artwork. The Dubship sculpture was created through a process that moved back and forth between real and virtual space: Ralph sculpted a physical maquette in plasticine, Jason scanned it into 3D, and we both remodeled it with VR sculpting tools in a 3D model of the atrium space. We used the 3D model of the sculpture to make templates for construction in metal and wire by hand. By now scanning the sculpture and bringing it into VR, we continue this play, returning the sculpture into digital space, reimagining it in the process. (We used a similar range of processes for our later project DS Tableau).

Ralph was exposed to VR sculpting tools with Rick at Eden Labs in Jozi, and by Jason at Ambient 3D in Cape Town. Eden went on to lead a series of weekly workshops with artists demonstrating the possibilities for them to use VR tools to produce work, and Jason and Ralph did similarly with artists in Cape Town.

Our ambition is to work with some of the wire artists with whom we collaborate for African Robots & SPACECRAFT, introducing them to VR sculpting tools and seeing how their facility with shaping lines into 3D forms translates into virtual space. One of the research ideas that has come from working with wire artists is the observation that they practice a form of topological ethnomathematics. The VR sculptures they make will form part of the environment of Digi-Dub Club.

More about Dubship I – Black Starliner (2019)

Dubship I – Black Starliner is an interactive, music-making spaceship sculpture on a monumental scale, produced through a collaborative process involving street wire artists, 3D designers, Virtual Reality sculptors, metal workers, musicians and electronic engineers, under the direction of multimedia artist Ralph Borland as part of his projects African Robots and SPACECRAFT.

The work plays on the history of Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey’s establishment of the Black Star Line shipping company a century ago, which was intended to take the descendants of African slaves back to Africa. Garvey is memorialized through dub music, in which space travel is used as a metaphor for liberation, transcendence and spiritual-political transportation.

The work has received good recognition: funded by the National Arts Council of South Africa; selected for exhibition by Azu Nwagbogu, director of the African Artists Foundation, while director of the Zeitz MOCAA; launched at the Zeitz MOCAA; selected as a performance lecture by the National Arts Festival South Africa; a performance lecture broadcast live on Chimurenga magazine’s Pan African Space Station; selected for exhibition at the Dakar Biennale 2020; awarded a small grant by the African Culture Fund; and an article forthcoming in Revue Espace(s) n°20, 2020, Éditions de l’Observatoire de l’Espace du CNES.

Listen to an archived recording of Ralph’s dub lecture broadcast live on Pan African Space Station in 2019: listen on Mixcloud.

The postponement of the Dakar Biennial 2020 has relevance to our proposal. Bringing the artwork to West Africa is one of our ambitions in reenacting the route the Black Star Line was intended to take. The challenges in exhibiting the work there, first in transporting a large-scale sculpture, and then in the cancellation of the exhibition as a whole due to the coronavirus pandemic, highlights the need for us to equip ourselves to travel in both geographical and virtual space.

Adding a shipping container to the assemblage of the sculpture makes it easier for us to store and transport it, and provides a secure, multipurpose auxiliary space for the work on exhibition. The conversations and events that take place around the sculpture are part of the work. It also presents the possibility of showing the work in Virtual Reality, in shared online spaces, where people can access these spaces from our custom VR portal housed in the shipping container.

For more information, see dubships.spacecraft.africa, download an overview document, check out the making-of video above, and give us a follow on @spacecraft.africa 🙂 For more about the continued relevance today of Marcus Garvey’s work with the Black Star Line a century ago, read below.

More about our take on Virtual Reality

Some theorists propose that dub foreshadows Virtual Reality, in conjuring imaginary spaces through sound by using powerful sound systems and echo and delay effects. Dub sound systems are meant to transport audiences to other spaces. We propose that our work on this project is a contribution to returning VR to African diasporic culture.

Interest in VR has waxed and waned over the last decade or two. It has come into increasing prominence this year with the physical isolation and restrictions on socializing and travel imposed by regulations addressing the coronavirus pandemic. Jason and Rick have been working in this realm for a long time, and have created several VRChat worlds and VR artworks, while Ralph has embraced its utility as a tool for visualizing and producing art while working with it intensively over the last two years.

VR has some obvious problems. One of the chief problems is probably accessibility, because of the specialized technology required to access it, which limits who can participate in it. We’ve been experimenting with some approaches to this, such as trialling WebGL 3D environments which can run in a browser, making 3D interactive environments at least (if not full VR) more accessible. It’s also worth noting that VRChat worlds can be accessed through an ordinary computer using monitor and keyboard – a special VR headset is not required (though desirable). Even these are becoming cheaper and more available as consumer-level technology.

In including the purchase of VR gear in our project, to set up VR access points, we are making some challenge to the problem of accessibility. Where we exhibit the physical work, we provide a way for audiences to access the VRChat world. We have included a VR headset sterilizing box in our budget, so that we can safely have many people using the gear in sequence. We are providing not just a VRChat world that exists in a virtual space, where anyone with a computer and internet connection can access it, but a physical technology station for entering it for the full VR experience.

In providing not one, but two sets of VR gear, and in working with the VRChat platform rather than traditional VR, we are addressing another problem with VR to date – social isolation in the user’s experience of it.

VRChat is an environment for shared experience in VR – where people can interact with others in VR. When attending a concert in VRChat, such as Jean Michel Jarre’s concert earlier this year, this is a typical possibility: Ralph and Jason logged into the concert world from Cape Town; Rick logged in from Johannesburg; and our friend Eoghan logged in from Dublin. We all hung out at the concert together in our avatar forms and real voices, navigating fantastical club spaces.

With Rick, we intend to make a particular contribution to VRChat, which is a universe in constant development. We would like to make an effort to promote across worlds in VRChat, borrowing from our experience of physical world club land and underground party promotion, where we would do hand-to-hand fliering at other people’s events to build our community. We will be visiting other worlds and talking about Digi-Dub Club, and inviting people to join us there, helping to build our profile and social possibilities of our space.

But why two sets of VR gear? This comes from experience: it’s fun to enter the same VRChat world together, particularly when experiencing it for the first time, as many people will be in our exhibition scenario. A person in real space can introduce you to the technology; if you have come to the exhibition with a friend, then the two of you can have a shared experience in VRChat. You can be companions with one another in a new space, and meet other people together, followed by a conversation in real space afterward.

This is the blending of experience in physical space and VR space that will become increasingly common as the technology, and our social experience of it, develops.

Wait, what’s Digi-Dub?

We’re glad you asked 🙂 Digi-dub is the name given to dub music which is made from synthesized electronic sounds, as distinct from earlier (and ongoing) dub music which was made using recordings of live musicians, to which electronic effects such as echo and reverb were later applied. Dub music originates at the end of the 1960s or early 1970s, depending on who you listen to, and digi-dub in the 1980s.

Digi-dub is associated with the ‘democratization’ of dub music, in that the means of production became more widely available. You no longer needed to be a professional music producer with expensive equipment and access to a studio, session musicians, or recordings of live acts. We can make parallels with Detroit techno, originating at around the same time, which was made on early Japanese electronic keyboards that had become available cheaply in the US; or more recently the Gqom sound from South Africa, which was first made on cheap PC software, and has since taken the world by storm. In all of these forms, the creativity of the producer makes something new from cheap technology that becomes available to them.

Digi-dub also has strong ties to the UK reggae, dancehall and dub scene, rather than direct from Jamaica. It came up from the children of Jamaican immigrants to the UK, and from a scene in which black immigrant youth mixed with white working class youths in the ska, punk and reggae scenes. It’s a particularly hybrid music form, bridging cultures, and marking the advent of the digital age, the start of ‘digital futurism’ and the soundtrack to battles fought between radical youth, far-right racist groups, and the police in 1980s Britain.

One of the iconic albums from this era is 1984 album The Dub Factor by Black Uhuru, mixed by Adrian Sherwood of On-U Sound, which grew out of the Rock Against Racism scene. One of our favourite albums, it refers to dub music by the name ‘bionic reggae’, cementing the idea of dub as a future-oriented, computer version of reggae.

The title Digi-Dub Club then is meant to capture the translation of the analog sculpture Dubship I – Black Starliner (2019) into computerized space, and to refer to this era of hybrid cultural, musical and technological fusion, and progressive politics, which led to today’s computer age and the myriad forms of electronic music available to us.

See The Everlasting Impact of Digi-Dub on Bandcamp.

The Black Star Line – 100 years later

The subject matter of Dubship I – Black Starliner, which refers to the work of the political activist Marcus Garvey and his establishment of the Black Star Line shipping company, and our proposal for its extension into social VR via Digi-Dub Club, resonates with our renewed global focus on society, culture and the economy, and the identification of both continued fault-lines of inequality, and movements for change, provoked by the Covid-19 epidemic of 2020.

Marcus Garvey’s activism a century ago was directed against the violent racism institutionalised in the United States and worldwide, and towards a global recognition of the rights of Africans and the descendants of Africans in the diaspora, through building economic and political power, and he used some methods that would be familiar today to achieve this, from crowd-funding the establishment of the Black Star Line, to media-savvy inversions of symbols of power (naming his Line to rival the dominant White Star Line for example).

The material of our project points to the provocative question of how far we have come in challenging injustice and division, and how much work still needs to be done – and what methods are available to do so. Where the work is shown it is accompanied by lecture and performance, and via Garvey’s memorialisation through reggae and dub music. This musical culture, which grew in Jamaica, is now a diverse global form, echoing between continents, as movements for economic and social justice are global and diverse too.

Our project explores the creative possibilities for digital technologies that enable remote access of artwork, and shared experience in virtual space. A motif for our work with African Robots and SPACECRAFT is the free passage of ideas. We aim to bridge boundaries and connect across spectrums: connecting popular culture with fine art, hand-craft with digital processes, art with technology, and physical place with virtual space. Our work connects across socio-economic and professional boundaries, bringing street wire artists into fine art spaces and artists into proximity with technologists. We aim to celebrate and elevate the understanding of an African vernacular artistic practice, and reconceive it through putting it in conversation with other forms.

Our focus is both local and global: African Robots has travelled to Brazil, holding workshops with wire artists and producing new interactive electronic wire art with them in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paolo, and to South Korea, where we worked with a local artist to make a new interactive wire frame work reflecting local subjects. Ralph and Lewis were selected for an art residency in France to share their wire art and electronics techniques with local artists and crafters, scheduled for 2020 – and now of course delayed until 2021.

This proposal for a modified shipping container to assist the transport of the physical sculpture furthers our goal to take our work across borders and engage in artistic exchange. As well as the Caribbean and the US as destinations for touring the work, we have an eye on Geneva, where a delegation from Garvey’s organisation, the UNIA, spent 3 months representing the interests of Africans in the diaspora to the League of Nations in 1922. We have the ambition of taking our work from there to Kassel, a day’s drive from Geneva, for Documenta in 2022, taking place a century after the UNIA’s visit to Europe – and the last year of operation of the Black Star Line.

Contributors

Ralph Borland is a multimedia artist who works across art, science and technology, often with a focus on social intervention. His undergraduate degree in Sculpture at the University of Cape Town focused on the production of large-scale sculptural installations incorporating multi-channel sound arrays. His Masters degree in the Interactive Telecommunications Program at New York University introduced him to the use of communication networks, computation and electronics for creative purposes. His thesis artwork Suited for Subversion (2002) a performance suit for street protest, came from his experiences as an activist, and was acquired by the New York Museum of Modern Art for their permanent collection. He completed a PhD in the Disruptive Design Team in the School of Engineering at Trinity College Dublin, producing a critique of design interventions in the developing world. His post-doctoral work at the University of Cape Town focused on public art and culture, and North-South knowledge inequalities.

His long-running interventionist art projects African Robots and SPACECRAFT engage with street wire artists in Southern Africa to produce new forms of wire art that marry vernacular art and craft practices with interactive electronics, VR and 3D-modelling. Their work was represented at the International Symposium of Electronics Arts in 2018 and 2019, and their monumental, interactive collaborative musical sculpture Dubship I – Black Starliner was exhibited at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art in 2019. Ralph is a frequent collaborator with Science Gallery International, which advances work at the intersection of art, science and design that addresses social issues.

Jason Stapleton works with a range of software including 3D animation, game engines and procedural generation tools. With these he creates abstracted digital worlds in which he seeks to question the boundaries between the virtual and the real. His primary mediums are video, 360 video, game, VR and AR. In these he explores various aspects of digital capture such as photogrammetry, lidar and traditional methods. His core interest is in VR, specifically virtual embodiment and how it relates to consciousness in its ability to inform our experience of consensual reality.

His recent work includes the creation and production of a standalone Augmented Reality application for artist Sue Williamson’s upcoming show at Fondazione Merz, Italy, which involved managing programmers, content creation and motion capture, and implementation of assets into Unity game engine. He conceptualized, directed and produced a 360 video for display on the Iziko Planetarium’s new dome projection system, using lidar scans implemented in Unity, which was selected for their Under the Dome festival, and subsequently by Melbourne Planetarium for their film festival.

Sean Devonport is a multi-talented musician, sound guy (and skate boarder) with a Masters degree in Computer Science from Rhodes University. Sean has worked with a number of artists and musicians to provide immersive sound. He engages with VR content creators, enabling them to implement realistic 3D audio experience. He is also a dub devotee, and has toured South Africa with his digi-dub outfit.

Lewis Kaluzi, Farai Kanyemba, and Franco Shidume are master wire artists who are highly skilled at shaping wire into complex 3-dimensional forms, and have collaborated on a number of mixed-technology wire art projects with African Robots and SPACECRAFT.

Rick Treweek is the co-founder of Eden Labs, an emerging technology R&D house which develops technology and shows for contemporary art. Eden is a catalyst for new technological approaches to artistic practice. Their aim is to provide artists with access to new and established technologies in an effort to educate and aid them in expanding their worlds through captivating and interactive storytelling with the use of mixed realities and other digital media. Rick is a creative technologist, who enjoys constantly pushing the boundaries of digital formats and disruptive hardware. With over 15 years of experience in the digital space, he explores emerging technologies and how they influence our reality. His practice centres around creating worlds within art, games and new formats of digital media.